A rain storm drives us into a bar after the opening. Sarah, an animated Australian is toasting Budweiser from shot glasses. She calls our lovely drinking mom “Tibetan Bjork” with her wide smile, porcelain skin and toddler son folded in her skirt.

The Chinese soldiers march outside the bar at midnight. Tibetan Bjork pauses, trying to recall last year’s riots. She looks away, her eyes wet as she stumbles to find the words. “The whole world saw,” Sarah tells her.

The music starts. The bar owner, a Tibetan musician with closely cropped hair and a long Chinese ponytail is strumming a three-stringed guitar and belting a low, throaty mantra. “It is a Chinese folk song—the mens—they know it,” our Chinese translator Ivy tells us.

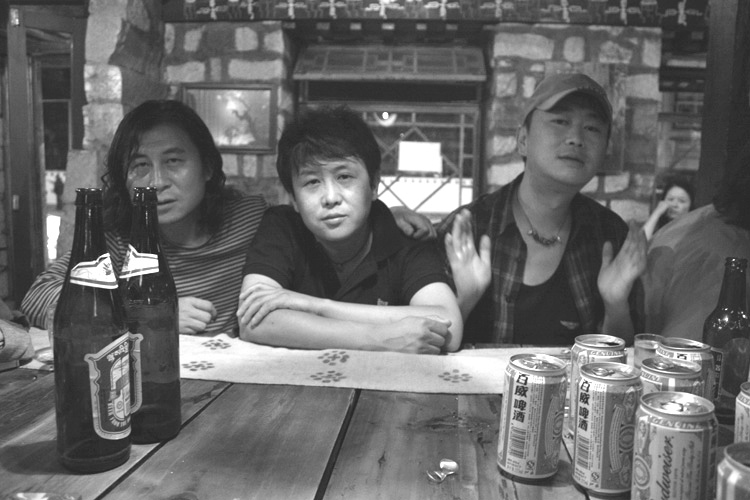

I am surprised. This is a Tibetan bar. I assumed they play Tibetan music. Then I realize that there are Tibetans and Chinese at our table. They are friends. They drink together and laugh together. They make and sell art together. Tibetan and Chinese, they are living and loving side by side.

< next >